Activator session: Mārama Stewart – uLearn21 from CORE Education Digital Media on Vimeo.

EdTalks – Mārama Stewart (Me)

I didn’t even know this was up! lol.

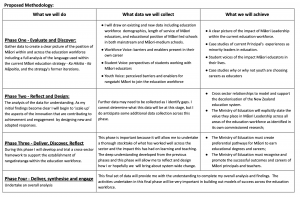

Assignment Number Two – Project Brief

The project brief is a preliminary description of the project you wish to complete as part of the programme. The purpose of the Project Brief is to provide a short summary of your proposed project and make a preliminary argument for why the project is desirable.

Learning outcomes for this assessment include:

-

Analyse and critique key literature relating to the organisational needs of the Māori sector.

-

Critically review theories and analyse strategies and approaches related to leading culturally responsive change in the Māori sector.

-

Explore assumptions and mental models that underline leadership roles and organisational structures in order to critically reflect on enablers and barriers to change.

-

Explore the political dynamics infusing Māori and Indigenous organisations.

My assignment:

The aim of this project is to decolonise the New Zealand education system through the following actions:

- The Ministry of Education must explicitly affirm the value of Māori Leadership across all areas of the education workforce as identified in its own commissioned research;

- The Ministry of Education must create preferential pathways for Māori to earn educational degrees and careers;

- The Ministry of Education must recognise and promote existing successful outcomes and careers of Māori principals and teachers.

Introduction – We Are Not OK:

The publication, the Hunn Report (1961), formally illustrated the global disadvantage of Māori within contemporary New Zealand society. This disadvantage is still prevalent within Māori society 62 years later with 2019 data showing that over a third of Māori leave school without Level Two NCEA. Retention rates for Māori are 12% lower than tauiwi (non-Māori). Term Two 2020 attendance rates for Māori dropped to 47.5%, 21.2% behind European students.

The “statistical blackhole” of Māori engaging in higher education (Hunn, 1961) has been corrected, however the picture it paints is bleak. In terms of attainment Māori continue to lag behind non-Māori in tertiary education qualifications.

The negative effects of low tertiary outcomes are clearly detailed in Nair and Smart’s 2007 report to the Ministry of Education. Those without a formal education qualification are ten times more likely to suffer from severe hardship in their living conditions as compared to those with a Bachelors level or higher qualification. The report concludes that the return on investment in tertiary education is significant on employment, income and improved health and lifestyle outcomes (Nair et al., 2007). All are areas where Māori feature significantly at the lower end of the statistics. Yet the latest data still illustrates the continued failings of the New Zealand education system to provide equitable outcomes for Māori (Jackson, 2016).

Tertiary Level Equivalent Full Time Students in 2019

Bachelors Degrees and higher

Total Students Enrolled – 167 840

European Students Enrolled – 92 205

Māori Students Enrolled – 18 360

Why Leadership Counts and Why Māori Leadership is Transformative:

Wagner and Kegan (2006) explain that our education system was not designed for the skills needed in today’s society. They propose that a new form of leadership is needed that grows the personal capacities of all members of an organisation. In fact they often refer to the leadership structures needed to transform our schools as leadership communities. Within these communities the leader becomes the mediator that encourages growth and new opportunities for learning, even when there are contradictions evident in the communities thinking (Wagner et al., 2006). The new transformational leadership model shifts away from the traditional capitalist model of leadership which priorities power and control (Wagner et al., 2006).

School Leadership and Student Outcomes: What Works and Why: Best Evidence Synthesis [BES] (Robinson et al., 2009) is a significant document which seeks to test the notion that “school leaders make a critical difference to the quality of schools and the education of young people” (Robinson et al., 2009, p.48). This Ministry of Education document indeed makes this connection between leadership and successful outcomes, and it also specifically differentiates Leadership from Māori Leadership and in fact goes one step further by differentiating Māori educational leadership from Māori-medium educational leadership. This is important because it identifies two distinct concepts:

- That Māori leadership is present and important within both the mainstream and Māori-medium educational settings – a point completely absent from all iterations of the Māori education strategy.

- Those tumuki (Principals) in Māori educational leadership positions and Māori-medium educational leadership positions have a disproportionately higher workload than their contemporaries due to the cultural and societal needs of their communities (Robinson et al., 2009, p. 70).

The qualities, skills, and priorities of transformational leadership described in Wagner and Kegan (2006) are imbued throughout Māori history both in pre and post colonial time periods. Katene (2010) states that the primary characteristic of good leadership is vision and the ability to bring one’s community along with that vision. The talents listed by Katene (2010), and synthesised by Mead (2006) to incorporate traditional values within the modern world are all mirrored in Wagner and Kegan’s book. Mead’s (2006) eight Māori leadership talents for today are also found within the five leadership dimensions found in the BES (Robinson et al., 2009, p.95). The research is clear that to be a Māori Leader is to be a transformational leader, the leader needed in today’s society.

An analysis of the Ministry of Education’s Māori Education Strategy:

The Māori education strategy (1999) has had three redevelopments since its launch in 1999. Through these developments it is interesting to analyse the evolution of the language used; in particular the use or non-use of the terms “authority” and its Māori equivalent “rangatiratanga”. These terms are important as described in the Waitangi Tribunal’s Te Whānau o Waipareira Report (1998).

Partnership thus serves to describe a relationship where one party is not subordinate to the other but where each must respect the other’s status and authority in all walks of life (The Waitangi Tribunal, 1998, p. xxvi).

This is reflected in the 1999 publication of the Māori education strategy

“To support greater Māori involvement and authority in education” (The Ministry of Education, n.d.).

The analysis of the evolution of the strategy into its current form Ka Hikitia – Ka Hāpaitia is fascinating as the term “authority” completely disappeared from two of the three rewrites. Most concerningly with in all three of the documents the terms ‘Māori Learners”, “Māori pedagogy”, “te ao Māori”, “Māori medium“, and ”whānau“ are all used to differentiated the diversity of the needs of Māori. The term “Māori Leadership” does not exist within the Ministry of Education’s premier Māori education strategy.

One must question why the Ministry of Education is unwilling to state outright that Māori Leadership is the transformational form of leadership needed to meet the needs of all learners in today’s society. The fact that the Ministry of Education commissioned the research which confirmed this as fact (Robinson et al., 2009) demands explanation.

Ka pū te ruha, ka hao te rangatahi – Cast the old net aside … :

Models of tauiwi organisations adopting Māori governance and leadership structures can be found throughout the New Zealand business landscape. Companies such as CORE Education Tātai Aho Rau have completely rebranded and created the successful Te Aho Tapu, Tiriti Honouring work programme to actively demonstrate their commitment to partnership and Te Tiriti o Waitangi. This is a private company which has built Māori Leadership into the fabric of their leadership and governance structures.

The Otago School of Medicine has enacted the successful “Mirror on Society” enrolment policy creating pathways into medical careers that were once unattainable by Māori unfairly disadvantaged by the effects of institutional racism (Jackson, 2016). The programme is built on the well documented benefits to society of having a socio demographically diverse health workforce as they will lead to better health outcomes for diverse populations such as Māori (Crampton et al., 2018).

These are just two examples of how Māori Leadership and diversity of workforce which must be recognised, supported, and actively recruited as change agents. The steps to replicate these policies and outcomes within the education workforce are not difficult.

The aim of this project is to correct the under representation of Māori in the Education workforce which will in turn enable Ka Hikitia – Ka Hāpaiti’s (2020) first key measure of success “Māori learners are engaged and achieving excellent education outcomes” (The Ministry of Education, 2020).

What is Good For Māori, is Good for All – Dr. Russell Bishop:

Moana Jackson (2016) states that “The education system still continues to fail so many of our mokopuna because that’s what it was designed to do” (Jackson, 2016, p. 41). The Ministry of Education’s continuous attempts to change the people within (the system), to create achievement for the people without, must be recognised as flawed. The overwhelming evidence of Māori Leadership success must be acknowledged, and built upon for the benefit of all learners in today’s society.

The aim of this project is simple, it is the acknowledgement and implementation of research that has existed for years. When The Ministry of Education officially acknowledges and places value on Māori Leadership they will be able to create preferential pathways for Māori into the education workforce through tertiary qualifications. The proven return on investment of a tertiary education will in turn create a forward momentum of positive outcomes for Māori. The entrenchment of Māori rangatiratanga within the framework of the New Zealand education system will reverse the cycle of poverty and hardship within one generation if those in control of the system, The Ministry of Education, are truly committed to their 30 year vision for education:

Whakamaua te pae tata kia tina – Take hold of your potential so it becomes your reality …

We are descendants of explorers, discoverers and innovators who used their knowledge to traverse distant horizons.

Our learning will be inclusive, equitable and connected so we progress and achieve advances for our people and their future journeys and encounters

Whāia te pae tawhiti kia tata – Explore beyond the distant horizon and draw it near!

(The Ministry of Education, 2020)

Bibliography

Crampton, P., Weaver, N., & Howard, A. (2018). Holding a mirror to society? Progression towards achieving better sociodemographic representation among the University of Otago’s health professional students. New Zealand Medical Association Journal, 131(1476), 59 – 69. https://www.nzma.org.nz/journal-articles/holding-a-mirror-to-society-the-sociodemographic-characteristics-of-the-university-of-otagos-health-professional-students

Hunn, J. K. (1961). Report on Department of Māori Affairs: With statistical supplement, 24 August 1960. Wellington: Government Press.

Jackson, M. (2016) Reclaiming Māori Education. In Hutchings, J., & Lee-Morgan, J. (Eds.), Decolonisation in Aotearoa: Education, Research and Practice (pp. 19 – 39). NZCER Press.

Katene, S. (2010). Modelling Māori leadership: What makes for good leadership? MAI Review, 2010(2), 1 – 16. http://www.review.mai.ac.nz/mrindex/MR/article/view/334.html

Mead, H. M.,(2006). Hui Taumata Leadership in Governance Scoping Paper. Wellington: Victoria University. Retrieved March 5, 2021, from https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/27440364/maori-leadership-in-governance-unitec.

The Ministry of Education. (n.d.). The Ministry of Education Te Tāhuhu o Te Mātauranga. https://www.education.govt.nz/our-work/overall-strategies-and-policies/ka-hikitia-ka-hapaitia/ka-hikitia-history/first-maori-education-strategy/

The Ministry of Education. (2020). The Māori Education Strategy: Ka Hikitia – Kapāitia. Wellington: Group Māori

Nair, B., Smart, W., & Smith, R. (2007, July). How Does Investment In Tertiary Education Improve Outcomes For New Zealanders? Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, (31), 195 – 217. https://www.msd.govt.nz/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/journals-and-magazines/social-policy-journal/spj31/31-how-does-investment-in-tertiary-education-improve-outcomes-pages195-217.html

Robinson, V., Hohepa, M., & Lloyd, C. (2009). School Leadership and Student Outcomes: Identifying What Works and Why. The University of Auckland.

Wagner, T., Kegan, R., Lahey, L., Lemons, R. W., Garnier, J., Helsing, D., Howell, A., & Rasmussen, H. T. (2006). Change Leadership: A Practical Guide to Transforming Our Schools (1st ed.). Jossey-Bass.

The Waitangi Tribunal. (1998). Te Whānau o Waipareira Report. GP Publications.

Assignment One for my Masters in Māori and Indigenous Leadership

Identify a recent media story* that in some way engages with Māori and/or Indigenous leadership. Discuss how that story displays elements of Māori leadership, as well as contemporary challenges to the nature and attributes of leadership that are needed within our communities at this time.

My first year as a primary school principal was in 2010. I was an optimistic 29 years old who was absolutely clueless about the complexities of leadership. During that time, the Ministry of Education had invested heavily into creating The First Time Principals Programme (FTPP). The programme would educate new principals in the “leadership practices that have the greatest impact on student outcomes” (Robinson et al., 2009).

The FTPP conference gathered over 200 first time principals from across Aotearoa. Conference speakers included the Minister for Education the Honorable Anne Tolley, Alice Apryll Parata noted principal, and Dr Vivianne Robinson, co-author of the Best Evidence Synthesis [BES] – School Leadership and Student Outcomes: Identifying What Works and Why. The speakers shared the same key message, Māori were disproportionately represented in the long tail of student underachievement. We, as school leadership, were the key to changing the statistics and we needed to do better for our Māori students.

A defining moment for me occurred as Apryll Parata spoke about Māori drop-out rates in schools. My neighbour (a middle-aged Pākehā woman) leaned over and asked “Well, what worked for you?” I replied, “Nothing, I dropped out too”. I remember her look of shock and non-comprehension as she responded “Oh, I thought you would have been one of the ones that did well at school.” I pretended not to hear her as I wondered if I was classed as a member of the long tail. I looked up at Parata, before casting my eyes wide and surveyed the 95% non-Māori new principals sitting in that room, and thought… “Well nothing’s going to get any better from this room while we (Māori) are excluded from the supposed solution”.

A heartbreaking revelation to have so early in my career. The combined potential influence in that room could have made a critical positive difference in the achievement and well-being of thousands of Māori students (Robinson et al., 2009). Yet less than half a dozen of the attendees knew what it was like to be Māori in a school in Aotearoa. My experiences there left me with the feeling that Māori Educational Leadership is not valued as an effective resource to challenge disproportionate underachievement in our schools. All the more frustrating when the Ministry of Education’s own literature specifically referred to Māori Educational Leaders as change agents capable of challenging existing power structures and becoming strong advocates for Māori students in their schools (Robinson et al., 2009).

As I look back, I wonder what kind of effect could have been achieved if even half of those first time principals had been Māori like me. This thought saddens me. Not once, since my pale inauguration into the world of principalship, have I seen evidence that the Ministry of Education has acknowledged the imbalance of non-Māori leadership versus Māori leadership in our schools today.

While the article I have chosen is not specifically situated within the education space, it is a tale of leadership, founded within Te Ao Māori. It spoke to me as it perfectly illustrated the potential for positive change which was lost in that room back in 2010. It answers the question; what would happen if Māori were empowered to lead as Māori, while facing the contemporary challenges found within today’s society?

The article from The Spinoff, entitled The story behind the fight to save Ihumātao is a retrospective interview by Justin Latif (2020) with Qiane Matata-Sipu. Matata-Sipu and her group of local cousins stopped a housing project, due to be developed on land stolen from the local indigenous community in 1865. Their efforts as Māori leaders restored that land, Ihumātoa to tangata whenua in 2021 (Latif, 2020).

Latif (2020) provides the reader with intimate insight into Matata-Sipu and her cousins’ development into a uniquely Māori style of leadership. Through their leadership, the Save Our Unique Landscape campaign (S.O.U.L) would grow to include thousands of members globally and lead to the occupation of Ihumātao. Historians, archaeologists, and academics, both Māori and non-Māori, supported the cause that would take the group to the United Nations, twice (Latif, 2020).

To understand how Matata-Sipu and her five cousins came to lead this group, it is important to understand the epistemology of Māori Leadership. In his paper, Māori Leadership in Governance, Professor Hirini Mead (2006) synthesises and modernises two lists of eight traditional leadership qualities by Te Rangikahake of Ngati Rangiwewehi, Te Arawa and Himiona Tikitu of Ngati Awa. He refers to these qualities as The Eight Talents for Today or Pumanawa (Mead et al., 2006).

The Eight Talents for Today:

-

- Manage, mediate and settle disputes to uphold the unity of the group.

- Ensure every member of the group is provided base needs and ensures their growth.

- Bravery and courage to uphold the rights of hapū and the iwi.

- Leading the community forward, improving its economic base and its mana.

- Need for a wider vision and a more general education than is required for every day matters.

- Value manaakitanga.

- Lead and successfully complete big projects.

- Know the traditions and culture of their people, and the wider community (p.10 ). (Katene, 2010, p.11)

Mead (1997) states that Māori Leadership must not only lie within one’s whakapapa, but also in the mandate given to them by the leader’s people. Matata-Sipu grew up on the pā at the feet of her grandparents surrounded by political conversations and governance decisions her grandparents made for her hapū (Latif, 2020). Through whakapapa and Mead’s (2006) pumanawa, Matata-Sipu and her cousins created a leadership network which gained the mandate to lead their people. The alliance they formed around S.O.U.L, became the key to creating momentum in the outside world. The leadership partnerships they formed strengthened their campaign to its eventual acknowledgement and concessions by The Crown (Latif, 2020).

In Latif’s article, each of the pumanawa organically appears as Matata-Sipu recollects the story of Ihumātoa and the networked leadership roles each of her cousins took upon themselves. We experience first hand the cousins’ growth into the mantle of leadership until we reach the climax of the occupation, the attempted eviction of the rightful owners of the stolen lands. The uniqueness and power of Māori Leadership can be seen in Matata-Sipu’s recollection of the day the New Zealand Police came to evict them.

“It was really emotional. Everyone was so upset, and as the sun set behind the police, I just fucking cried my eyes out. I was thinking about all the kids, and what they had to see and then also thinking about our grandparents, and all they had done for this place. I was mourning for everything we had lost over generations, for our tūpuna, for our whenua.

“And I thought about my grandfather and how he wouldn’t have let this happen, and as I looked at the sunset, and the maunga, and my nieces singing, I cried out to my tūpuna, saying to them, ‘we need you to be here right now, if we ever needed you – we need you right now’.”

And in that moment Matata-Sipu found the strength she needed. (Latif, 2020)

Crisis surrounded Matata-Sipu and her cousins. It was from that moment and her connection with her tīpuna that she was able to find the courage and commitment to succeed. The article When Leadership Spells Danger, Heifetz and Linsky (2004) discusses the contemporary theory of leadership which forms around to two different types of leadership challenges – technical challenges and adaptive challenges (Heifetz & Linsky, 2004).

Technical challenges prescribe to the common misconception that the sole requirement of leadership is expertise to resolve the problems we face, not unlike a mechanic fixing a car (Heifetz & Linsky, 2004, p.35). Technical challenges are an easy managerial fix, they involve seeing a simple problem such as a gap in communication and a simple fix such as forming a Facebook group to reach a global audience. In fact, the entire campaign for Ihumātoa was founded via a clear and concise Facebook post written by Matata-Sipu in 2015 (Latif, 2020).

The challenge which Matata-Sipu faced as she stood in defiance of the police eviction was anything but a simple technical fix. The incredibly complex problems Matata-Sipu and her cousins beheld that day were born out of the same colonising tools the crown had designed to subjugate Māori since the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840 (Walker, 2016). The tools which allowed the theft of mana whenua and subsequent vilification of Matata-Sipu and S.O.U.L for fighting for return of that mana whenua (Muru-Lanning, 2020) are the same tools which are still manipulated by those in power “to maintain an unjust social order between Māori and Pakeha” (Walker, 2016, p.20).

Heifetz and Linsky (2004) call these kinds of incredibly complex problems adaptive challenges. Adaptive challenges often involve leadership living up to their convictions; “to closing the gap between their espoused values and their actual behaviour” (Heifetz & Linsky, 2004, p.33). What we see in Latif’s article is that Matata-Sipu and her cousins understood instinctively that the “solutions to adaptive challenges lie not in technical answers, but rather in people themselves” (Heifetz & Linsky, 2004, p.35).

Colonisation and its effect on the lives of Māori through multiple generations has been compounded by successive systemically racist government policies which have created a problem so complicated that the adaptive leadership capabilities needed to solve them seem almost insurmountable (Walker, 2016). Since the 1960 Hunn Report on Māori Affairs, subsequent investigations have frequently found that the gaps between Māori and European health, education, wealth, employment and economic development have all deteriorated (Walker, 2016).

Yet within the story of Ihumātao we see contemporary Māori Leadership force one of Aotearoa’s largest listed companies (Fletcher Building, n.d.) to backing off from their lucrative deal, and a once resistant government buying out that building giant. In fact, Matata-Sipu and her cousins are just one iteration of Māori Leadership successfully counteracting the colonial tools of subjugation created by the crown (Walker, 2016). Sir Apirana Ngata, Sir Peter Buck, Dame Whina Cooper, Ranginui Walker, Sir Mason Durie, Sir Tipene O’Regan, Hanna O’Regan and Dame Tariana Turia to name just a few are all incredibly successful people, facing complicated, adaptive challenges, and meeting those challenges using Mead’s (2006) eight pumanawa.

I have been a primary school principal for twelve years now a Leading Principal according to the career structure in my collective agreement. Last week I attended the Whakatane Principals’ Association meeting. Not all 25 members were in attendance, but it was my pleasure to help welcome the fifth Māori member to our association. I am still the minority Māori in the room.

Twelve years on from my conference nothing has changed for Māori. According to Education Counts 2019 data shows that over a third of Māori students are leaving school without Level Two NCEA. Retention rates for Māori are 12% behind the total number of students at 69.6%. In Term Two 2020 attendance rates for Māori dropped to 47.5%, while COVID-19 is a factor which should not be discounted, it is still 21.2% behind European students.

Schools are still not serving the needs of Māori students despite the millions of dollars spent on Māori achievement strategies in schools over the last 16 years. The 2013 – 2017 Māori Education Strategy Ka Hikitia – Accelerating Success (Ka Hikitia) focused on teaching the teachers how to support Māori students to enjoy and achieve educational success as Māori (The Māori Education Strategy, 2013).

Ka Hikitia has five guiding principles. One of which states the following:

Māori students are more likely to achieve when they see themselves, and their experiences and knowledge reflected in teaching and learning. (The Māori Education Strategy, 2013, p.3)

Of the 61,000 teachers working in this country, only 7,403 identify as Māori. These strategies have not worked, and nor will they ever work because a non-Māori teacher, principal, educator will never understand what it is like to be Māori. Just like how that middle aged white woman could not comprehend that the first time principal seated next to her was a high school drop out. A non-Māori will never have the same connection to whakapapa nor understand that our connection to our tīpuna is not of the past but very much present in our now.

Further evidence of the positive effect of Māori students seeing themselves as normal in the classroom is provided in Dr Vivianne Robinson’s BES (2009) where she describes the challenges faced by educational leaders in tackling wide spread disparity amongst students:

A second challenge is to markedly improve educational provision for, and realise the potential of, Māori students. Recent national data suggest that Māori-medium schools are better serving Māori than English-medium … (Robinson et al., 2009, p.36)

Within this context it is important for the reader to know that the ethnicity of over 95% of Māori Medium teachers is Māori. Within Māori Medium schools Māori students see themselves as normal, and their normality as Māori reflected back at them through their teachers.

Until our tamariki can see that reflection surrounding them and nurturing them and staring right back at them kanohi ki te kanohi (face to face) they will never enjoy and achieve educational success as Māori. This barrier has been created because 7,403 Māori teachers spread between 2,563 schools is only an average 2.8 teachers per school. That’s not many for the 200,000+ Māori students enrolled in 2020.

Matata-Sipu and her cousins changed the course of a multi-billion dollar company versus a tiny iwi south of Auckland in less than half the time that it took for all of our current Māori achievement strategies to fail. Matata-Sipu and her cousins proved that Māori Leadership that is deeply rooted in Te Ao Māori enabled them to be strong, connected and innovative, and ultimately to achieve success. Their ability to create a uniquely Māori network of leadership where responsibility was shared and talents strengthened by that network reinvigorates my own personal approach to leadership.

If the Ministry of Education was genuinely committed to its espoused values found within its own Māori Education Strategy (2013) then they must enact these values in its actual behaviour. The Ministry must follow the above clearly stated and well researched phenomenon of Māori Leadership. It can not continue to ignore the knowledge and evidence and refuse to act upon that evidence when forming policy. Our tamariki have been disadvantaged for far too long.

Bibliography

Heifetz, R. A., & Linsky, M. (2004, April). When Leadership Spells Danger. Educational Leadership, 61(Leading Tough Times), 33-37. http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/apr04/vol61/num07/When-Leadership-Spells-Danger.aspx

Walker, R. (2016) Reclaiming Māori Education. In Hutchings, J., & Lee-Morgan, J. (Eds.), Decolonisation in Aotearoa: Education, Research and Practice (pp. 19 – 39). NZCER Press.

Katene, S. (2010). Modelling Māori leadership: What makes for good leadership? MAI Review, 2010(2), 1 – 16. http://www.review.mai.ac.nz/mrindex/MR/article/view/334.html

Latif, J. (2020, December 18). The story behind the fight to save Ihumātao. The Spinoff. https://thespinoff.co.nz/atea/18-12-2020/the-story-behind-the-fight-to-save-ihumatao

The Māori Education Strategy. (2013). Summary of Ka Hikitia: Accelerating Success 2013 – 2017. The Ministry of Education.

Mead, H., (1997). Landmarks, bridges and visions: Aspects of Māori culture. Wellington: Victoria University Press.

Mead, H. M.,(2006). Hui Taumata Leadership in Governance Scoping Paper. Wellington: Victoria University. Retrieved March 5, 2021, from https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/27440364/maori-leadership-in-governance-unitec.

Muru-Lanning, C. (2020, December 19). The truth about Ihumātao: All the false claims and misinformation, corrected. The Spinoff. https://thespinoff.co.nz/atea/19-12-2020/the-truth-about-ihumatao-all-the-false-claims-and-misinformation-corrected/

Robinson, V., Hohepa, M., & Lloyd, C. (2009). School Leadership and Student Outcomes: Identifying What Works and Why. The University of Auckland.

Coping with Change – Great Videos

These are two different kinds of change but excellent advice and can be used together at different points of the process.

NOTES:

- Be realistic about the change you to make make it small and do able. “Don’t look at the whole mountain, focus on the first six steps”.

- Commit a small time focus to reflect – as often more effective to large financial boosts.

- Listen to the neigh sayers and the feedback and the criticisms but keep to your compass – your values.

- Acknowledge what is not working – and let it go.

- Don’t makes the ‘solution’ and then look for the problem (google glasses).

- You must share … talk, learn and interact.

- Should I do this thing?

- Does it scratch my itch?

- Would I still do it if it took twice as long? (You can only have two of the three – Cheap, Fast, Good).

- Would I still do it if it cost twice as much?

- Would I still do it if I used my own money?

- Do I have a realistic plan and timeline?

- Am I ok with failure?

NOTES:

How to get past the “it’s not going to happen wall”.

Not real reasons:

- “It’s always been like this”: It means the problem is older than you think it is.

- “It’s the same everywhere”: the problem is broader and wider than you think.

- “It’s not in the budget”: it means we’ve spent the money in the wrong places.

- “It’s not in the charter”: the people who were supposed to provide the vision weren’t thinking as big as you.

- “It’s political”: “I’ve learned to keep my ideas to myself.”

- “It’s just traditional”: “Actually, I don’t know why we’re doing this, but it’s always been that way.”

Five most classic reasons people resist change:

“I’m scared of the transition, not the idea.”

Helping people moving through the transition – three normal phases ‘the Negative – Interesting – Positive’

“I’m scared of the transition. I’m not scared about the idea.”

Everyone is scared of the unknown – keep people informed “yes it’s going to be bumpy and scary but we will get there”.

“I don’t know how big a deal this change really is.”

Transition is moving through Four Doors:

The first door are the things that we used to be able to do and can still do. I’ll get people to write a list.

Door number two are the things that we couldn’t do before and we still can’t do.

Door number three are the things that we could do before and we can’t do now.

You can for door number four. That’s a door that’s only recently opened. These are the things that we couldn’t do before but we can do now. It means I can make my job suit my lifestyle.

“I don’t see how I fit into any of this:

You give them authorship. You empower them to design the change for themselves. Suddenly they’re not responding to change, they’re taking control of change.

The tool: What did you keep? What did you chuck? What did you change? What did you add?

“Yeah, but people hate change.”

The truth is they want real change. They’re sick of believing something that isn’t real. They want something genuine. Questions to ask …

Is the change real or fake?

Is the change cultural or structural?

Is the change offered of foisted?

When working with a cynical, closed groups …

You can keep things the same or you can make a difference. But you can not do both. That is the choice you have to make. I’ve made mine, you choose yours.

What are the characteristics of the best leader you’ve worked with to date?

I wonder if he will ever read this …

I wonder if he will ever read this …

Mr David Reardon – Former Principal of Russell Street School.

David was famous for wall papering his DP’s entire office with colour photocopies of The Muppets. I believe his photocopy budget was much higher than ours. Another time he minded the entire school, for some strange reason I can’t remember, and showed the kids really stupid Youtube Videos that I don’t think anyone else would have got away with. He’s more comfortable in shorts than a tie.

He knew you well, and he knew what you could do better than you did yourself. He created opportunities for his staff to thrive. He made so many of us leave. From my ‘cohort’, three of us are successful Principals, and three are DPs in large schools, one is an ‘Across School Teacher’ and two others are Team Leaders.

He taught me to always make your Office Manager a cup of tea in the morning, and that a staffroom should be brimming with laughter, delicious food, and a room full of equals where you can sit down and chat with anyone.

We got him a good once during our special announcements at morning tea. There were four of us young women on our staff around ‘child rearing’ age. One by one we each stood and announced the impending birth of our first child. OMG his face was hilarious, his look of genuine joy for us morphing into disbelief as you could see him calculating his potential staffing disaster. I think by announcement number four he was starting to cotton on but when our 89 year old librarian stood up to announce her pregnancy the whole staff just lost it (they were all in on the joke). You could see the relief wash over his face … but still double checked with us that we were actually joking. A very thorough leader lol.

He had a stern conversation with me once as a second year teacher. I had gone away for the weekend and had come back late Sunday night. I was exhausted and rang in sick Monday morning. On Tuesday, I can’t remember his exact words, but he made it clear that I had a responsibility no only to the kids but to our staff, our team. I needed to suck it up and get through because my slacking off put additional pressure on our team. I was so ashamed I had let him down. His conversation made me a better person.

He is kind and he would never make anyone do anything he wouldn’t do himself. He is more than happy to let others shine, in fact he encouraged it. He is hard working, honest, and funny. He knew me and how important my family is to me, and he helped me to shine. Thanks David.

Once Again Sleep Is For The Weak

I’ve decided to post my study reflections and assignments for my CORE Education, Advanced Leadership Programme.

I’ll try and post any accompanying media if it is public creative commons. Otherwise if I can’t I’ll just bold and link the name to anyone I reference. Here are my first two assignments for the Introduction Module:

Assessment One:

Watch the video from Bill George (Professor of Management Practice at Harvard University).

Now tell the group:

Who are you?

My name is Mārama Stewart. I am my ninth year of principalship and second school. I came by principalship by accident really. I was bored waiting in my classroom for my next mid-year parent teacher conference. I had been at Russell Street School in Palmerston North for the last three years and was very happy collegially but wanted a different challenge. I was a good classroom teacher, but it was not my passion. I was browsing the Edgazette and I saw a vacancy for a Principal with ‘Attitude At Altitude’. It looked cool. I asked my friend whom was acting principal at the time if he thought I could do it. He said yes, and I said why not. In January 2010 I began my career as a Sole Charge Principal 30 minutes north east of Taihape with 12 kids between the ages of 5 and 12. After two and a half years and one ERO Review I accepted the principal position at Waiouru School. I have been at Waiouru School for six years now.

How well do you relate to what Bill has to say about leadership and lifelong learning?

I like what Bill said about getting out to meeting interesting people and seeing different cultures, engaging with different ways to lead. It makes you, I think, reflect on what is really powerful and what I just do out of habit. I think it is important, with what he said about trying to see yourself from the eyes of others. What kind of person, what kind of leader am I in there eyes, and does it mirror what I think I am.

What kind of leader do you aspire to be?

I would like to be an Innovative Leader who creates an environment where people are able to grow to be the best they can be.

Assessment Two:

For any professional development and networking process to succeed, you need to have some clear objectives.

What is an example of a professional challenge you currently face or think you may face in future?

My current professional challenge is the intersections of two phases of my career. The first that we are wrapping up our Teacher Led Innovation Fund Project and we are now at the report writing and dissemination phase. The second is that at the end of this year I will qualify as a ‘Leading Principal’ on my career structure.

Both of these phases will take me out of my comfort zone of leader in my school and our Waiouru community to leading at the next level. I will need to be able to disseminate the findings of our research at the Leadership level and to now ‘develop leadership in others’.

What do you want to achieve from participating in the Advanced Leadership Programme?

While I find the actual act of being a leader in my school and community quite easy, I seem to just do it naturally. I’m not actually sure in academic terms what it is I am actually doing. This has of course caused a bit of a road block for me for developing leadership in others. I really want to use this programme to understand what it is that defines an Innovative Leader. By learning about Leadership I hope it will help prepare me to take on the up and coming takes of the two phases I spoke of above.

What do you need to get the most from the programme?

To analyse who I am as a Leader to make sure that what I think I am, is what others are seeing in me.

Well I Got Published

So I saw this article … https://thespinoff.co.nz/politics/06-06-2018/these-education-reforms-put-the-sector-at-the-precipice-of-disaster/

It made me grumpy so I wrote this article … https://thespinoff.co.nz/society/15-06-2018/why-must-schools-be-immune-to-innovation/

The thing is, up until I saw my writing up in ‘print’; published by an actual media outlet I quite like, I didn’t actually realise that I am quite a good writer.

Writing has never particularly appealed. I didn’t engage with it at school with any enthusiasm and I don’t think I ever was formally taught how to write beyond assignment feedback at University.

Seems like if you find a purpose for it, and you practice at it, one can actually become quite good at something with minimal teacher interference … ;-P

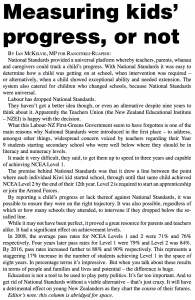

A Reply to Ian McKelvie, MP for Rangitikei

When Measuring Kids is More Important than Educating Them.

By Mārama Stewart, Principal of Waiouru School

A response to Ian McKelvie’s article “Measuring Kids’ Progress, or Not”, Ruapehu Bulletin – 15 May 2018

One of the perks of being a Member of Parliament, is that for some miraculous reason, most of the drivel you write for the media tends to become gospel. Furthermore, this ‘expertise’ doesn’t seem to require any qualifications or experience working in the profession you are commenting upon. As our local MP, ‘apparently’ you know it all. ‘Apparently’ you know even more than the 47 000 principals, teachers, and support staff that make up the membership of the Teachers’ Union (the New Zealand Educational Institute – NZEI).

I’ve been a bit busy lately and I’m afraid I didn’t get the chance to read our little local paper that week, well not until one of our teachers pointed out this article during our research project’s lead teachers conference.

You see we had been talking about the relief we are all feeling now that “Labour had dropped National Standards”. Gone was this ‘imperfect’ system which has been having a detrimental effect on all young New Zealanders over the last ten years. Then we see this article, Mr McKelvie’s opinion piece, Mr McKelvie’s comedy of errors.

We were seriously wondering if we had missed a calendar month or two and it was actually April 1st! His entire first paragraph seemed to come straight from Opposite Day – that day is actually celebrated on January 25th, so it could be that! Which one of our 47 000 Teacher Union Members did he actually speak with to form this opinion? Maybe he couldn’t find us, as a point of note for the future – you can find us with your children and grandchildren, your nieces and nephews, your best friend’s sons and daughters, and the kids down the road at your local in schools.

Our school is on Ruapehu Road in Waiouru if you want to come visit Mr McKelvie. At our school we will tell you that National Standards did not provide a “universal platform … to track a child’s progress”. Mr McKelvie, National Standards were not “universal”. They were not “easy” to use and did not “determine how a child was getting on at school”. They did not show progress or identify “when intervention was required or alternatively, when a child showed exceptional ability and needed extension”. Mr McKelvie, they did none of the things you asserted in your poorly informed opinion piece.

But then again, how would we know? We are not politicians who can magically turn opinion into fact. Why would we know that Mr McKelvie was wrong? Well probably because we the that have actually read the growing body of research and evidence that emphatically states that the National Standards were not good for our tamariki. In fact this school is has been part of a rigorous research project which shows that

Unfortunately for the 47 000 members of the Teachers Union, explaining why the National Standards system did not work does not fit neatly into a 60 second sound bite in the news, or an easily consumed half a dozen paragraphs in the local newspaper. You actually can not simplify Education into neat and tidy ‘standards’ that children will meet at specific points in time. It is a lifelong developmental journey which must encompass the whole child, their whanau, their culture and their place in their community.

But don’t just take my word for it, don’t ever just take what you read in the newspaper as gospel. Demand evidence that what you are reading is factually correct and come from experience, research, and evidence. So here is my evidence that Mr McKelvie is wrong. This is an extract from the Key Findings from the report “NZCER National Standards Report – National Standards in their Seventh Year” by Linda Bonne of the New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

-

Concern was evident about the negative effects on those students whose performance is labelled as ‘below’ or ‘well below’ a Standard and whose progress is not visible in terms of current reporting practices. To a lesser degree, there was also concern about students who perform well above a Standard not having their high achievement acknowledged, using the existing terminology of simply being ‘above’ a Standard.

-

National Standards seemed to have little to offer students with additional learning needs. Concern about the negative effects of labelling these students’ performance—often as ‘below’ or ‘well below’ National Standards over the long term—was particularly clear. Few agreed that National Standards help with the inclusion of students with additional learning needs. Some principals and trustees were concerned that including National Standards data for students with additional learning needs in their overall school data lowered their results, leading people to think the school was not performing as well as it was.

-

“Education is not a tool to be used to play petty politics”. It’s far too important to ignore the research, the evidence, and the 47 000 voices working everyday with our tamariki. To do that will have a detrimental effect on young New Zealanders as they chart the course of their future.

Blog Slacker, But a Busy Lady

I shall bullet point the growth in my life since my last blog post:

- Completed my Modern Learning Curriculum course through CORE Education and loved it. Took tonnes of notes and have dragged my staff along for the ride.

- Successful TLIF school, and now we are drawing to the end OMG. It’s been amazeballs.

- Had a Principal Sabbatical and learnt a lot about the power of Te Whariki and ECE pedagogy – why are we not grabbing onto that train I say!!

- Had a baby – Miss Ngāhuia – she’s one year old in two more sleeps. She’s delicious.

- Was horribly ill the whole pregnancy – was about as much use to everyone as tits on a bull. But that’s done. NO more!

- Went back to work, had to arrange an Au Pair at the last minute, learnt that two kids is not double but quadruple the work.

- Sorted out myself and learnt how to be a working mum again.

- And finally was accepted to the CORE Education, Advanced Leadership Programme – only 20 places nationwide!

- Oh and committed myself to write a Leadership Journal – at least 15 minutes every day. This was my first one… done.